What do you see when looking at an antique painting? You will probably say that you see colours, composition, some message. But can you see that the image is cracked? Have you ever wondered where these cracks are coming from? Have you ever thought that there are people who actually study these cracks?

I bet a dollar to a doughnut that most people reading this text wondered at school “why do I need physics?”. Personally, I will always associate this subject with a high school teacher who, with her dispassionate voice, tried to entertain us with “real-life examples”. One of them was an ant moving in uniform rectilinear motion on a gramophone record. I rarely managed to follow the topic of the lesson; usually, I just rolled my eyes and begin mind-wandering about basketball or football. It’s a shame, because with a bit of goodwill I could have got more out of these lessons.

Today I have a physicist in front of me (or rather on my computer screen, as we are talking via MS Teams) who is applying his knowledge in this field to a very specific task (I will explain that a bit further). However, is he still a physicist sensu stricto? I’m familiar with his academic achievements, his previous jobs and the project he’s now involved with, and I have to tell you frankly that I don’t know how to define who am I dealing with.

On the one hand, he’s a professor of physical sciences and member of the staff of the Jerzy Haber Institute of Catalysis and Surface Physiochemistry of the Polish Academy of Sciences (at the very beginning of the interview, we jointly concluded that this name was unmemorable), who began his scientific career at the Department of Atom Optics at the Institute of Physics of the Jagiellonian University. This sounds a bit as if he’s working in a super-secret centre and developing a plan to either destroy the world or save it.

On the other hand, in the past he was, among other things, head of the LANBOZ research laboratory at the National Museum in Kraków. He also directed the Sustainable Conservation Laboratory at Yale University. He’s member of the International Institute for Conservation of Historic and Artistic Works and the Scientific Council of the Museum of Photography in Kraków and was member of the Scientific Council of the National Museum in Kraków. This, in turn, sounds more pleasant and so artistic.

Physicist? Art historian? Conservationist? Artist? More likely the first one, but as it turns out, the answer isn’t so obvious.

prof. dr hab. Lukasz Bratasz

Being a pioneer

"We’re physicists, chemists, engineers by formation, but we’re actually representatives of a new scientific discipline that isn’t yet well recognised in Poland. It’s called heritage science" - explains professor Łukasz Bratasz, who heads the Cultural Heritage Research group at the Institute of Catalysis and Surface Physiochemistry of the Polish Academy of Sciences, in material prepared for Pionier TV.

"It is a science that uses the tools of disciplines such as physics, chemistry, engineering sciences or life sciences to answer questions posed by the humanities, most often represented by the discipline of art history or conservation" - the professor explains in the same material.

He points out that his team is primarily concerned with the interaction of heritage sites with the environment and then identifies three main research themes.

First, there is the process of dust transport and deposition on the surfaces of art objects, which leads to their accelerated soiling. In 2021, the conservation of the Wit Stwosz (Veit Stoss) altarpiece in St Mary’s Basilica in Kraków was completed. One of the reasons for why it had to be carried was the soiling caused by dust deposition.

A group of scientists led by professor Bratasz is also studying contemporary materials, such as synthetic polymers, for example plastics. They are used as material in contemporary art objects, such as, for example, in Tadeusz Kantor’s sculptures. These types of materials seemed to be very durable, but they actually they aren’t durable at all: over time their colour changes and cracks begin to appear.

The third and most extensive research topic is the process of mechanical damage to the works of art, such as paintings or sculptures, and how the process of crack formation is influenced by variations in the relative humidity. This research is important, for example, for museums, which spend important funds on air-conditioning equipment and the energy required to maintain certain conditions, such as temperature and humidity, in their premises.

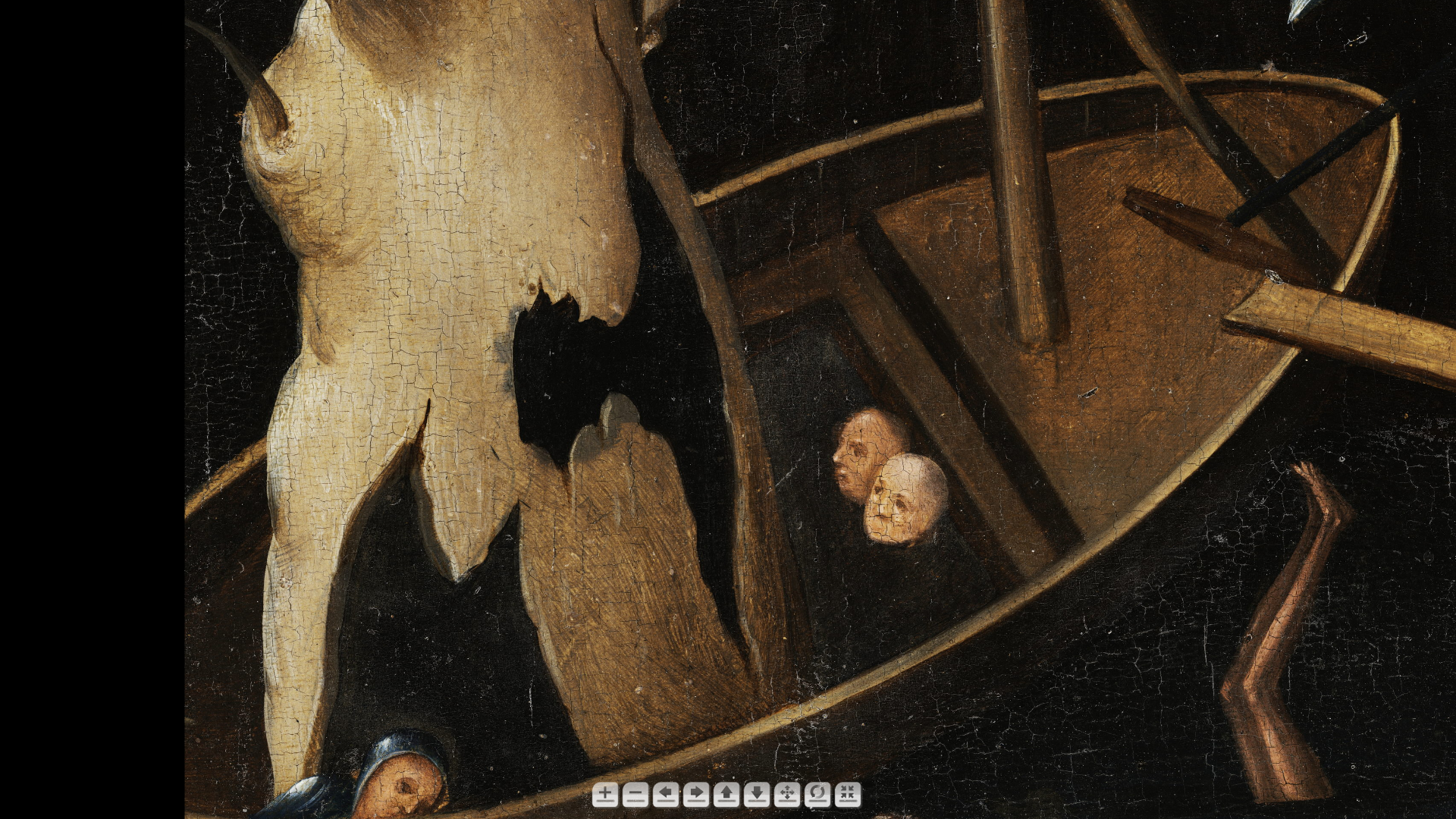

Detail of the painting "The Last Judgment", painted by an imitator of Hieronymus Bosch in the 16th century. Visible cracks

Is all this really necessary? This question will be answered in a moment, as the biggest part of our conversation was dedicated precisely to the third research area. Why was that? Because the group led by the professor is conducting its research in this area with the support of the EEA and Norway Grants.

Too expensive

"On the one hand, we have museums that precisely control the environmental parameters in order to protect their collections from damage. On the other hand, many heritage objects have survived to the present day and have been stored, for example, in historic churches where there is no microclimate control at all. Let’s take the example of St Mary’s Basilica, where the temperature varies from 0 to 30 degrees on an annual basis and the relative humidity from 30 to 90 per cent" - notes professor Bratasz.

His team is investigating whether such a highly restrictive approach to humidity control in museums owning paintings of great historical and cultural value is really necessary. This is verified by examining the cracks in historical paintings.

"We don’t mean that relative humidity isn’t important at all, it is rather about rationalising the energy consumption. Climate control processes are very expensive, while museums have limited resources. Until 2018, I worked at the National Museum in Krakow and I can tell you that the annual cost of energy consumption related to climate stabilisation was equivalent to employing 65 conservationists. These funds could be used for other purposes, such as increasing fire protection" - explains professor and adds:

"We want to review this very restrictive approach to microclimate management. Conservators will probably tell you that there are objects in museums that are very sensitive to changes in humidity. And that’s absolutely correct. The problem is that there are, let’s say, a million objects in the National Museum in Kraków, but few of them are actually threatened by fluctuations in relative humidity".

This issue also has an ethical aspect. The question is whether, in the era of anthropogenic climate change, we can afford to act excessively.

"I was once walking down the Nowy Świat Street in Warsaw and saw a beautiful banner on the gate of the Academy of Fine Arts saying ‘There will be no art on a dead planet’. And that’s bluntly true" - says my interviewee.

What the crack are all about

OK, but wait. What cracks? What humidity? What paintings?A few words of explanation in layman’s terms.

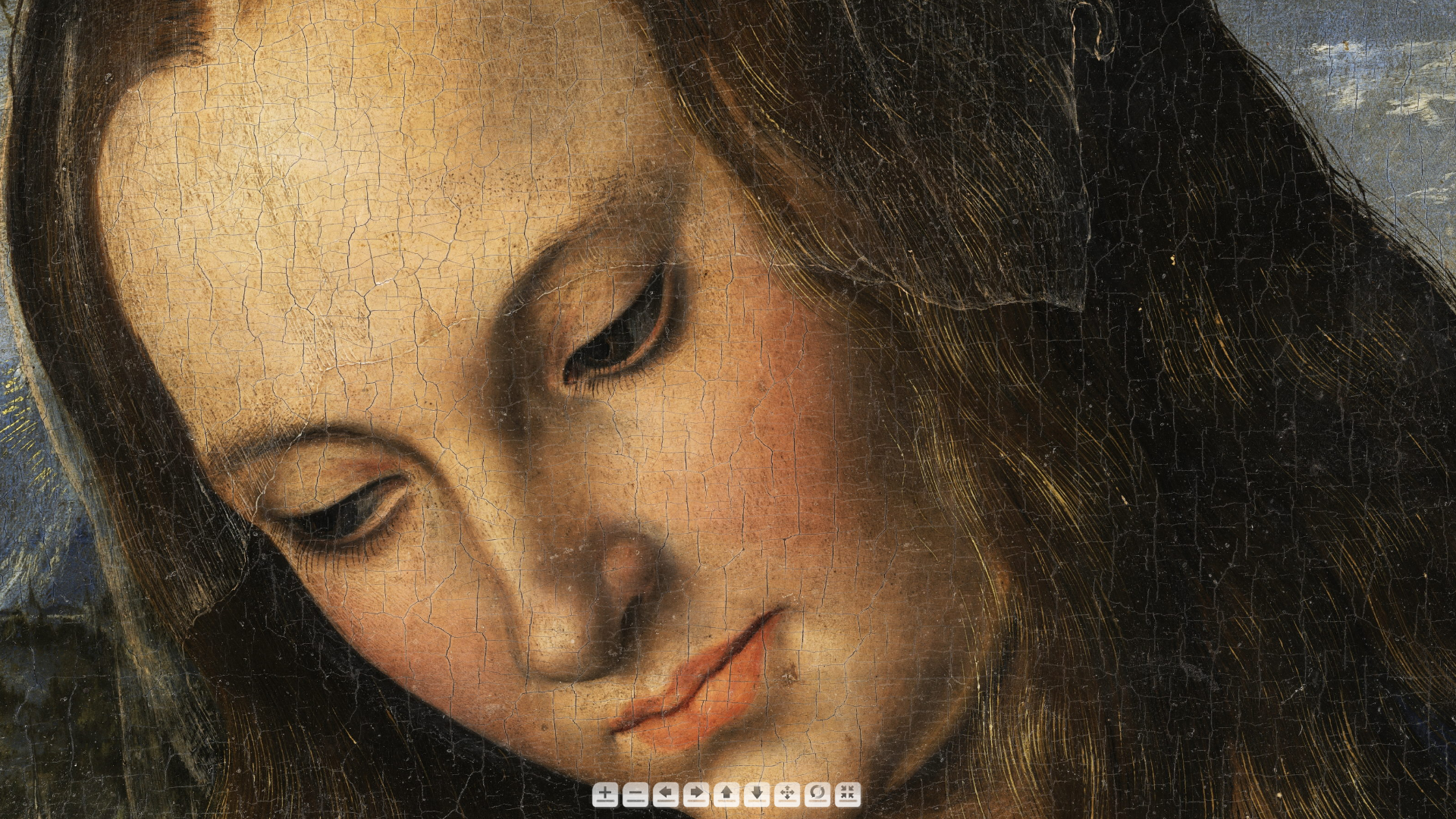

Have you ever wondered how a painting, such as one painted on a board from a few hundred years ago, is constructed? First, we have a wooden support. Its surface is covered with animal glue (the boiling of animal skin creates collagen glue). Then comes another layer, i.e. the mortar, which is a mixture of chalk, gypsum with animal glue. Only on top of all this are the layers of paint applied. And let’s not forget that there are different types of paints. In the Middle Ages, for example, the most common was tempera paint, in which egg yolk acts as the binder of pigments (the substances that give the colour). It was also possible to mix different techniques, e.g. The Last Judgement, a triptych by the Dutch painter Hans Memling, which will, by the way, run through my conversation with the professor, was done in tempera and oil techniques.

The painting "The Last Judgment" by Hans Memling

In historical paintings from several hundred, but also several decades ago, characteristic cracks, reflecting different patterns, appear. These cracks are called cracquelure. They result from the fact that different layers of the painting store energy and thus stresses occur (physics once again!), which must somehow be discharged. When the stress exceeds the critical point, a fracture occurs.

The parameters of these cracks, such as the shape, depth or patterns they form, are influenced by various factors, primarily the materials used. The crack patterns will differ depending on the use of tempera paint or oil paint. Craquelure has a different shape in Italian painting, a different shape in Flemish painting and a different shape in French painting.

"For example, the crack grids in the paintings of Flemish painters from the 15th century are very repetitive, because the guilds at the time controlled strictly the quality of the paintings and the work of the painters. In the Italian painting, such control didn’t occur" - explains professor Bratasz.

It can be cheaper and more efficient

It is here that we get to the heart of the matter. The research that underpins the very strict conservation guidelines, which include moisture, took into account the criterion of the first crack.

"I participated in this research personally. We would take, for example, a painting on a board that imitated a Leonardo da Vinci painting, apply a layer of primer on the painting layer, put the imitation in a climate chamber and watch when it would crack for the first time. Cracks were already appearing at small fluctuations in relative humidity of the order of 10%" - says professor Bratasz.

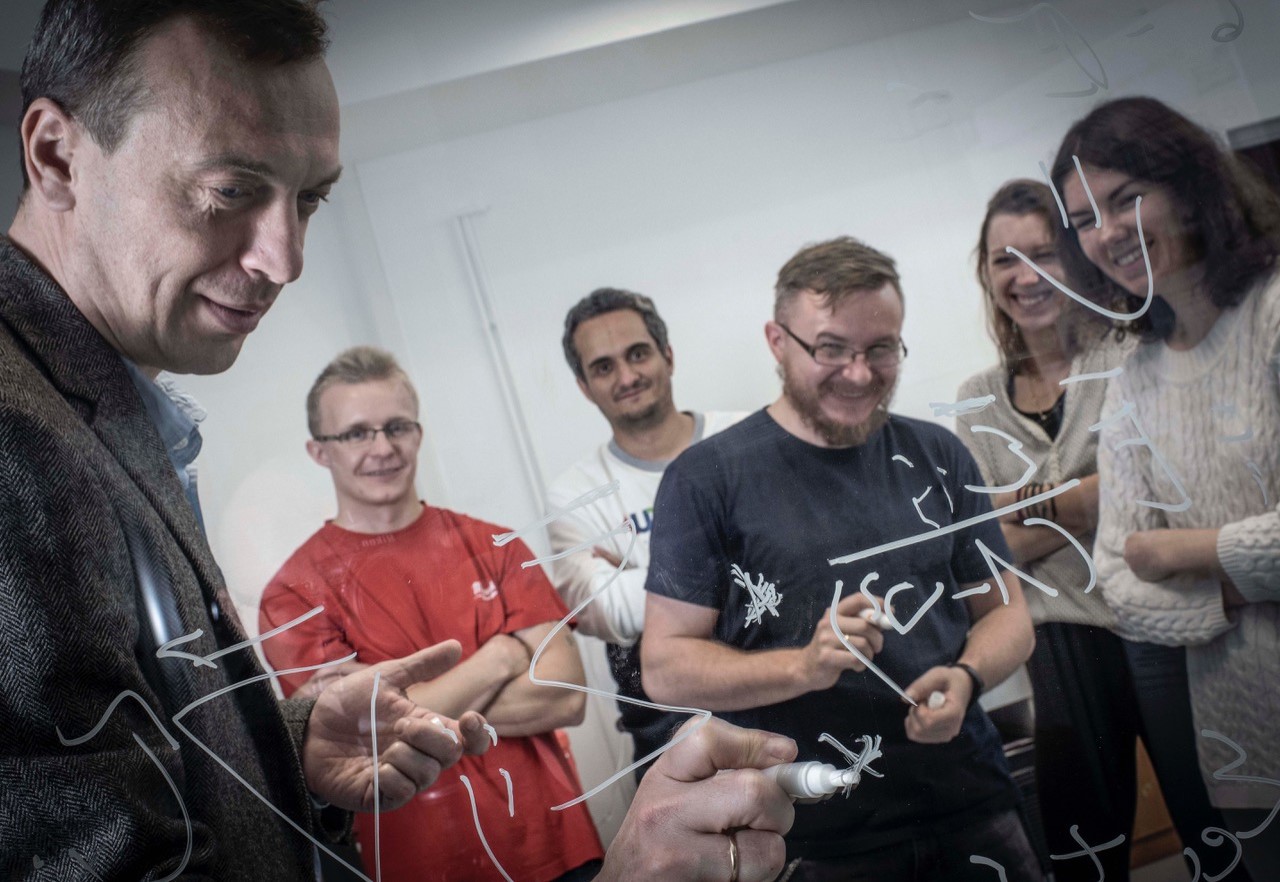

Professor Łukasz Bratasz with his team

However, he stresses that the criterion of the appearance of the first crack is not appropriate, as the paintings of greatest value, found in museums or galleries, are, after all, already cracked. For hundreds or decades, they were kept in places where climatic conditions were not taken care of at all. Professor Bratasz shows me a large close-up of the aforementioned Hans Memling painting The Last Judgement. The researchers scanned it with a scanning microscope and, indeed, they discovered a beautiful grid of cracks.

"If you ask me whether relative humidity can destroy a painting that is not yet cracked, the answer is yes. But if you ask me the same question about the enlargement of an existing crack network due to fluctuations in relative humidity, then the answer is often no. Apart from contemporary art objects, which generally are fully resistant to relative humidity, all of these historical objects that are the subject of our research have been stored for decades and hundreds of years in unstable conditions" - the professor points out.

It appears that these unstable conditions caused the craquelure, but this happened maybe a few or several years after the image was taken, and then the crack grid was already stable, despite the fact that the image was still stored under unstable conditions. A comparison of several hundred archive photographs with the current state of the objects by the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam showed that no new cracks had developed.

"This gives room for optimising conservation guidelines" - says professor Bratasz.

In other words, the guidelines are often too restrictive, resulting in unnecessary energy consumption by the microclimate control equipment. The professor’s research shows that paintings that have long since cracked do not tend to crack further even with large fluctuations of the relative humidity. They can be protected at a much lower cost – both cheaper and less damaging to the environment.

"Our research shows that when we have a dense grid of cracks, the fluctuations in humidity do not increase the size of the grid. We can say that these cracks are saturated" - concludes the professor.

A fragment of the painting "Madonna under Firs" painted in 1510 by the German painter Lucas Cranach. Visible cracks

Proper maintenance

There are, of course, exceptions, for example when a drastic conservation treatment is performed.

"If we flood these cracks with a material that is very hard, we recreate the sensitivity of these objects to fluctuations in relative humidity. On the other hand, if a painting is hanged in a museum, even if we use a drastic conservation method, the painting will not crack, because there the relative humidity is well controlled" - explains professor Bratasz.

He says that, together with conservators from Valencia, Copenhagen and Rome, they are preparing an application for funding from the European Union for research on art conservation. They want to explore how different conservation methods ‘sensitise’ objects and then evaluate them in terms of environmental friendliness. This will also make a difference to the museums. If conservation measures are carried out correctly, museums will not have to control the climate very strictly and will thus will be able to save energy.

Science teaches a lesson

I ask the professor if, in this case, he does not feel that with his research he actually teaching a lesson to other scientists who had carried out the research on which the restrictive conservation guidelines are based. In a sense, the findings of the professor’s team are telling: “you have been wrong for all these years”.

"In fact, I’m teaching a lesson to myself because I participated in that research. We now want to remove the scientific argument, which was correct many years ago, but now seems to us too simplistic" - says professor Bratasz.

Computers in the service of art

I am very interested in the technical aspects of the professor’s team operation. What methods do they use in their research? Before the talk, I had read that PAN scientists use computer models, but I hadn’t fully understood all the intricacies.

"We drew inspiration for the ideas from geological models, where we have virtually infinite stresses in the rock layers because there are gigantic forces acting on them. The planet is simply stretching them out" - explains professor Bratasz and adds:

"When engineers want to test the strength of a bridge, they build a model. They check, for example, how thick the beam must be for the bridge to bear a given load. We do exactly the same. We use engineering methods and image modelling software and look at what level of relative humidity the image will start to crack".

The thing is that professor Bratasz cannot translate engineering methods into his research on an equivalent basis. Engineers enter the name of the material into their software and see, for example, that a certain type of steel has certain properties.

"I can’t do such thing, because no one knows the material properties of the oil paint in Leonardo’s painting from 500 years ago" - he explains.

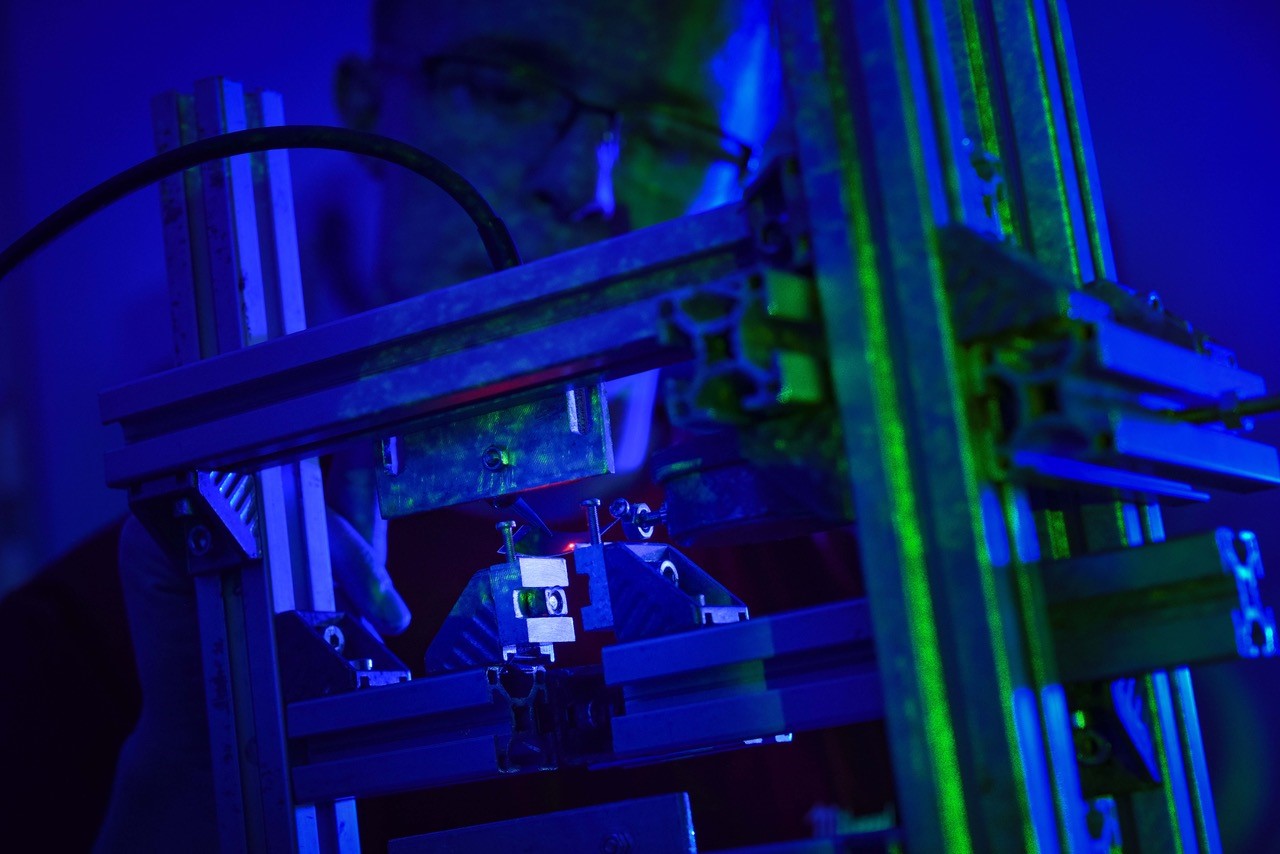

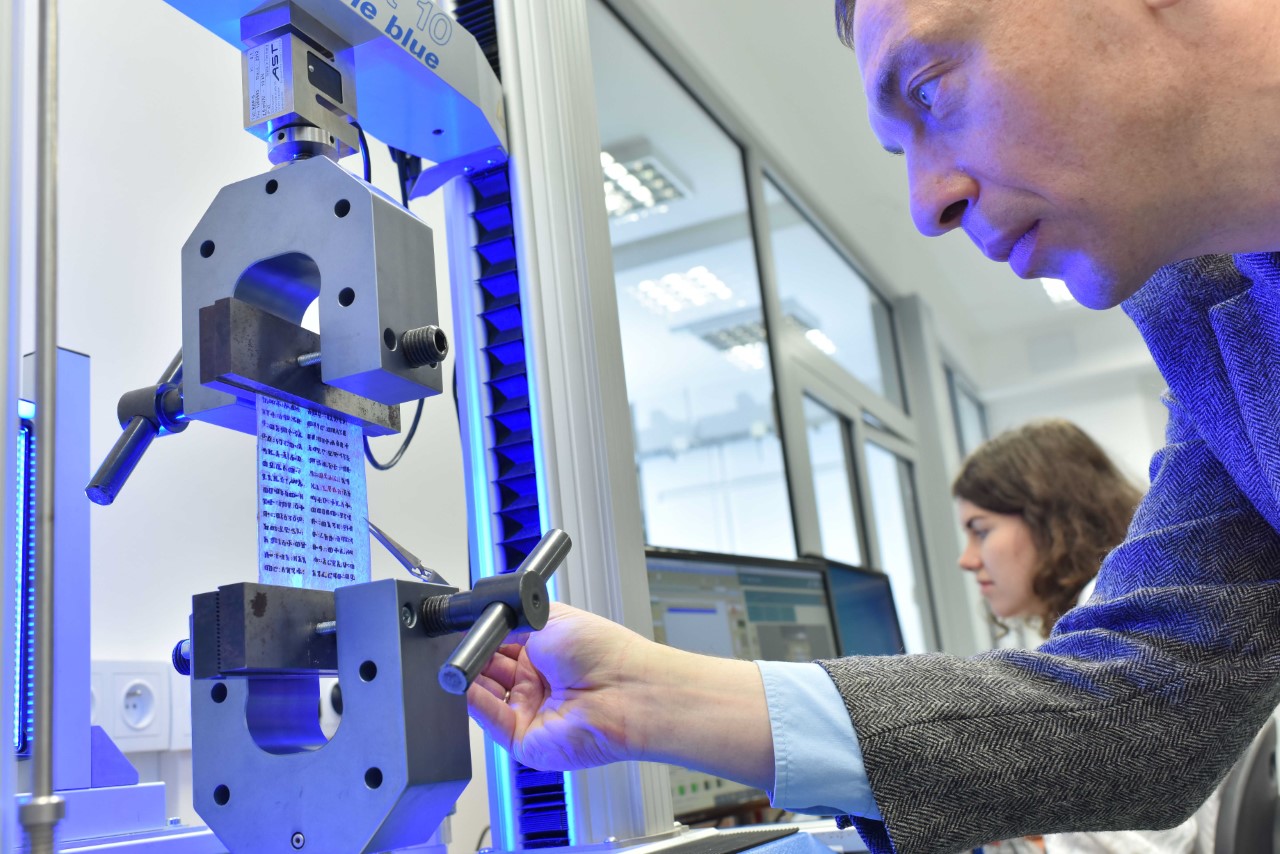

An employee of the Polish Academy of Sciences - Arkadiusz Janas - measures the shrinkage of the world's oldest samples of oil paint

In addition, there is a great deal of uncertainty as to exactly what materials and techniques were used to paint a particular picture and what is its history. Different important issued may include: whether the artist experimented, whether he stored the materials properly, whether the board he used has knots.

"That is why we use software to build a model of the object, which we call the Representative Virtual Object. It represents the worst possible case, that is, for example, the use of the most moisture-sensitive type of wood or the most fragile component of the paint layer. Such cases are unlikely to occur because the artists knew that the materials used mattered. If the humidity change is safe for this worst-case scenario, it is also safe for all other objects" - explains professor Bratasz.

"Our models are heavily overestimated, but the engineers also overestimate the strength of the bridge so that it does not collapse due to snowfall, for example" - he adds.

Scientists from the Polish Academy of Science also use real paintings.

"They serve us to check that the predictions of the computer models are correct. The issue is whether the crack nets are similar in the model and in reality" - says the professor.

A world class achievement

It all sounds a bit bizarre to me and is unlikely to have anything to do with an ant moving in uniform rectilinear motion across a gramophone record. I understand that the results of the research carried out by the professor’s team will be of relevance to museums or, in a broader context, to environmental conservation as such. However, raw data alone is not enough. I probably wouldn’t understand them anyway. Conservationists, by the way, are not physicists either. That’s why I ask the professor what will be the outcome of the project. Do they plan to publish some kind of a study for conservationists?

"That’s correct, we aren’t only interested in doing basic research and publishing the results in scientific journals. My group is very much involved in creating standards and guidelines. We created European standards, I was personally involved in the creation of the manual by the American Society of Heating, Refrigerating and Air-Conditioning Engineers, which produced a handbook for regulating environmental conditions in museums, libraries, galleries and archives. I hope that the results of our research will also make their way into this textbook, as it happened with our previous work" - states professor Bratasz.

The second tangible outcome, for which the professor wants to obtain funding from the Getty Foundation (a Los Angeles-based foundation that awards grants for projects in the field of art conservation, among other things), is the development of a proprietary IT tool that professor Bratasz’s team has developed. It is called HERIe – the Digital Preservation Prevention Platform.

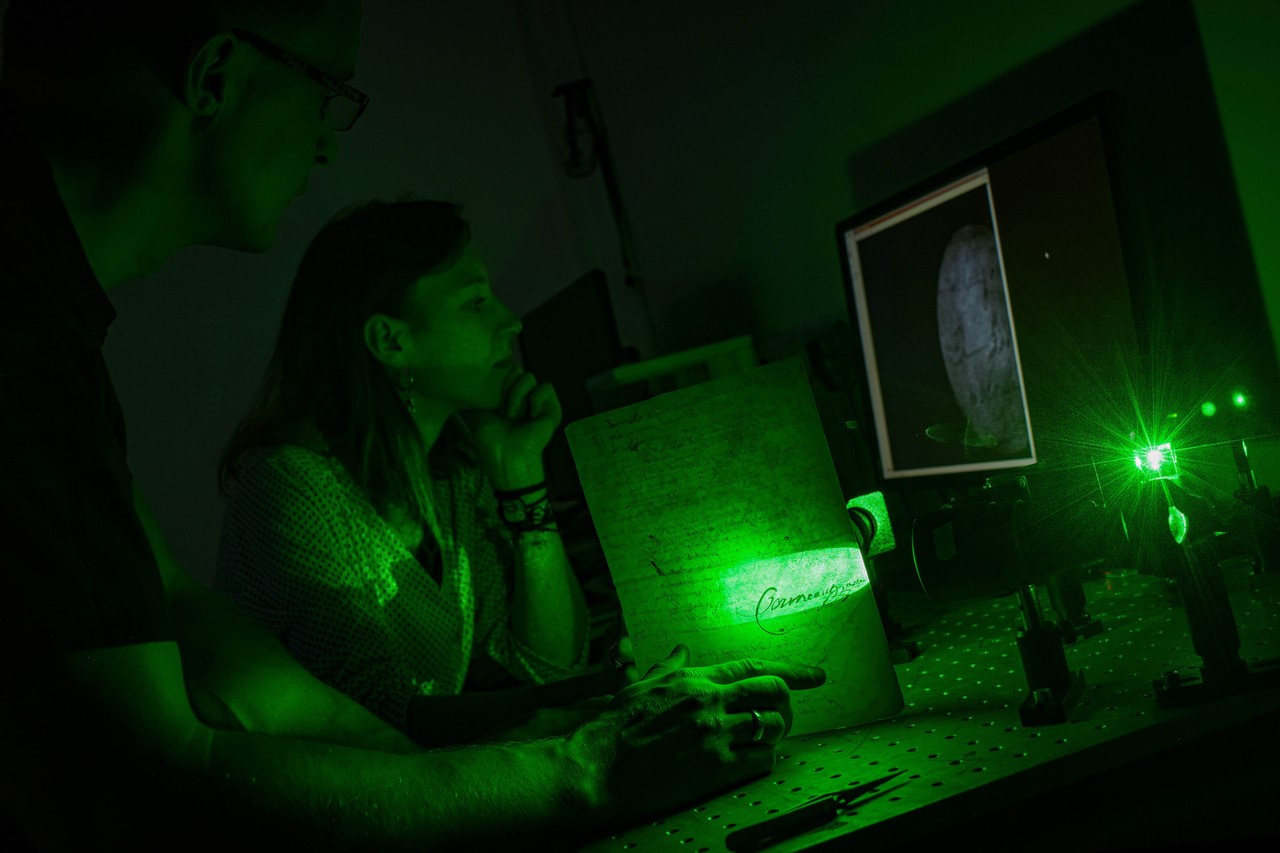

Noemi Zabari and Arkadiusz Janas (both from the Polish Academy of Sciences) use a speckle interferometer to study the detachment of decorative layers

"This platform is a worldwide achievement. It’s the largest platform for conservators and caretakers of collections in the world, and it was created by us from scratch, but it also draws on research from leading institutions that support the preservation of collections, such as the Canadian Conservation Institute and the English Heritage Foundation. HERIe allows conservationists to see what the results of different studies mean in practice and to make decisions based on that knowledge" - says the professor without even hiding his excitement.

He shares with me his screen and shows me how the platform works, using the effect of light on colours as an example. He selects some colour, changes the light dose, time and probably a few other parameters. At the end, I see a slightly different colour, already altered by the light.

"I have a database of the lightfastness of the materials, which have been measured by the Canadian Conservation Institute based on the dyes used historically. We can assess how this light affects the colour change over a given period" - the professor emphasises.

Research results on the effect of moisture on cracks in paintings will also be entered into the database, but the tool offers much more potential, as it is designed to help with risk assessment. Humidity or light are just two of the many factors that affect the condition of artworks. Others include, for example, temperature, the presence of pests, radiation, crime or fire.

It’s easier together

The list of project partners includes the Academy of Fine Arts in Kraków and the Norwegian University of Science and Technology in Trondheim. I ask the professor about sharing different roles in the project. It turns out that collaboration is key to success.

"Sure. It is a terrible ordeal to have a job that is approached without emotion. I have the great privilege of interacting with works of art and shaping the pioneering field of study. It warms my heart. In this small area I can make an impact on the world and, like any scientist, I want to be on top. It’s beautiful to be an apostle of a new discipline" - he states.

It’s great to hear someone say that their work brings them joy. This isn’t at all obvious, as the professor, to cite his own words, began to deal with his field somewhat by chance.

"The preparation of samples of tempera paints by Dr Aleksandra Hola was a huge support. Painting something is one thing but another is to prepare a sample. As a result, we are now preparing the world’s first publication to describe the mechanical properties of tempera paints" - says Professor Bratasz.

Dr. Aleksandra Hola from the Academy of Fine Arts in Krakow and Professor Łukasz Bratasz from the Academy of Fine Arts in Krakow prepare samples of tempera paints

Inflatable works of art

The project, funded by the EEA and Norway Grants, is focused on the research into the cracking of paintings, but the team led by professor Bratasz is also investigating other materials, such as polyvinyl chloride and linden wood. Works of art have also been and continue to be created from them. For example, the sculptures of Tadeusz Kantor were made from polyvinyl chloride, and the altar of Wit Stwosz (Veit Stoss) in St Mary’s Basilica in Kraków is made from linden wood. Hearing about the properties of these materials and the work of the team of scientists makes me feel at least like the protagonist of Arthur C. Clarke’s 2001: A Space Odyssey or, why not, Christopher Columbus taking his first steps in the Bahamas. For me this theme used to be complete terra incognita but now the grey fields on the knowledge map are slowly beginning to fill in with colour.

Polyvinyl chloride has been used in the arts since around the late 1950s, and in Poland it began to be widely used in the 1970s. It turns out that synthetic polymers, such as polyvinyl chloride, are not only used to create objects of applied art and fine art, but also, for example, for cable insulation. For both cable insulation and artwork, the so-called plasticisers are added to polyvinyl chloride: these are substances that make the material flexible (without plasticisers, polyvinyl chloride would be a very rigid material). The problem is that over time the plasticisers volatilize from these objects. This causes discolouration, the surface of the works becomes tacky, so they catch dirt and eventually crack.

Professor Bratasz’s team is working on a strategy to protect polyvinyl chloride objects. The scientists try to answer questions about, for example, their transport or storage.

"A lot of these types of works are inflatable. The Pompidou Centre in Paris, for example, displays inflatable armchairs designed by famous architects. The question is how to store them? When inflated, they are too big. Can they be safely stored without being filled with air? What will then happen on the bends? These are the kinds of questions we’re trying to answer" - explains the professor.

He tells me, by the way, an interesting anecdote which shows that the field his team deals with is de facto at the borderline of different scientific disciplines.

"In the first attempt, our project submitted to the National Science Centre was rejected because the commission considered that this project should be submitted in the polymer engineering panel. The problem is that we don’t make new polyvinyl chloride, we look at how aged polyvinyl chloride behaves" - he says.

Another material studied was linden wood. Professor Bratasz’s team is dealing with it mainly with the protection of the Wit Stwosz’s (Veit Stoss) altarpiece in St Mary’s Basilica in mind, but the problem is much wider.

"Massive wooden objects are very sensitive to changes in relative humidity, because they produce moisture differences" - he explains.

For example, the outer layer of the sculpture is dried out and the inner layer is wet. This also affects destruction.

The second problem is the properties of the linden wood, which need to be measured accurately and then verified with experiments.

"From the perspective of an engineer, linden wood is not an important material at all. You won’t find its property in textbooks" - explains the professor.

The different conservation guidelines, or rather their inconsistency, also pose a challenge.

"Historical buildings, such as churches, are more and more often made available for concerts or weddings. Such a building then needs to be heated, which means that the microclimate inside will change. German guidelines, for example, say you have to do it slowly and gradually, while Danish guidelines say you have to do it very quickly over a period of no more than eight hours" - recounts my interviewee.

Professor Łukasz Bratasz and Magdalena Soboń from the Polish Academy of Sciences during the examination of historic parchment cards

What warms the professor’s heart

The professor talks about all these things with great passion. So, I ask him if he still finds his work fascinating.

"Sure. It is a terrible ordeal to have a job that is approached without emotion. I have the great privilege of interacting with works of art and shaping the pioneering field of study. It warms my heart. In this small area I can make an impact on the world and, like any scientist, I want to be on top. It’s beautiful to be an apostle of a new discipline" - he states.

It’s great to hear someone say that their work brings them joy. This isn’t at all obvious, as the professor, to cite his own words, began to deal with his field somewhat by chance.

"I did my PhD at the Jagiellonian University and was on a six-month scholarship in the United States. It was a difficult period of separation from the family. After the PhD, there was an opportunity to go to work again in the States, but without the family. I decided to stay. I then got a job at the Polish Academy of Sciences" - explains my interviewee.

He stresses that he is also very much driven in his work by the great team of young people he works with.

Manifestation of the existence of God

I was talking to the professor straight after having read Zygmunt Miłoszewski’s novel Priceless, the plot of which is based on the search for the lost painting by Raphael Santi entitled Portrait of a Young Man. The characters in the novel were ready to sacrifice a lot to find this painting. Therefore, at the end, I couldn’t help myself and asked the professor about his favourite painting.

"That changes with as I get older. Just as Proust’s In Search of Lost Time should be read in one’s forties, I appreciated different painting at different stages of my life. Recently, I have been enthralled with the Italian painter Jacopo Pontormo" - he says.

He is an Italian artist, representative of mannerism, who worked in the 16th century.

However, the professor shows me straight away a scanned fragment of Memling’s The Last Judgement again. The painting used to hang in St Mary’s Basilica in Gdańsk and is now part of the collection of the National Museum in Gdańsk. It’s huge. It’s a triptych, which means that it consists of three parts. The central part is 242 by 180.8 cm and the wings measure 242 by 90 cm each.

The professor draws attention to the light reflections that can be seen on the tear of one of the sinners.

"The image was hanged high. Attention to such details made no practical sense, as no one had the right to see it from below. Memling must have believed that the perfection of this work acts as a manifestation of the God’s existence" - enthuses professor Bratasz.

"The Italians in the Renaissance had a conception of truth as synthetic truth, their paintings are often simplistic, they don’t show the details, whereas Flemish painting from this period can be characterised with these reflections in the smallest tear painted with the belief that the truth hides in the details" - he explains

and I can’t decide whether I’m more impressed by Memling’s painting or by the passion with which the physicist talks about art...

The project ‘Model of paintings with craquelure patterns for evidence-based climate control in museums’ is funded by the Norwegian Financial Mechanism for the period 2014-2020. The project budget is just over PLN 1 million.

References:

- Pionier.tv footage cited in the text dedicated to the work of professor Bratasz’s team - pionier.tv

- Information about the project on the website of the Cultural Heritage Research Group - heritagescience.edu.pl/grieg/

- Project description on the website of the National Science Centre - heritagescience.edu.pl/grieg/

- Project description at www.heritageresearch-hub.eu/project/grieg-craquelure/

Author of the text: Paweł Nowak (Communication and Promotion Team, Department of Assistance Programmes of the Ministry of Development Funds and Regional Policy)